Abstract

Nuclear charge radii are sensitive probes of different aspects of the nucleon–nucleon interaction and the bulk properties of nuclear matter, providing a stringent test and challenge for nuclear theory. Experimental evidence suggested a new magic neutron number at N = 32 (refs. 1,2,3) in the calcium region, whereas the unexpectedly large increases in the charge radii4,5 open new questions about the evolution of nuclear size in neutron-rich systems. By combining the collinear resonance ionization spectroscopy method with β-decay detection, we were able to extend charge radii measurements of potassium isotopes beyond N = 32. Here we provide a charge radius measurement of 52K. It does not show a signature of magic behaviour at N = 32 in potassium. The results are interpreted with two state-of-the-art nuclear theories. The coupled cluster theory reproduces the odd–even variations in charge radii but not the notable increase beyond N = 28. This rise is well captured by Fayans nuclear density functional theory, which, however, overestimates the odd–even staggering effect in charge radii. These findings highlight our limited understanding of the nuclear size of neutron-rich systems, and expose problems that are present in some of the best current models of nuclear theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The charge radius is a fundamental property of the atomic nucleus. Although it globally scales with the nuclear mass as A1/3, the nuclear charge radius also exhibits appreciable isotopic variations that are the result of complex interactions between protons and neutrons. Indeed, charge radii reflect various nuclear structure phenomena such as halo structures6, shape staggering7 and shape coexistence8, pairing correlations9,10, neutron skins11 and the occurrence of nuclear magic numbers5,12,13. The term ‘magic number’ refers to the number of protons or neutrons corresponding to completely filled shells. In charge radii, a shell closure is observed as a sudden increase in the charge radius of the isotope just beyond magic shell closure, as seen, for example, at the well-known magic numbers N = 28, 50, 82 and 126 (refs. 5,12,13,14).

In the nuclear mass region near potassium, the isotopes with proton number Z ≈ 20 and neutron number N = 32 are proposed to be magic on the basis of an observed sudden decrease in their binding energy beyond N = 32 (refs. 2,3) and the high excitation energy of the first excited state in 52Ca (ref. 1). Therefore, the experimentally observed strong increase in the charge radii of calcium4 and potassium5 isotopes between N = 28 and N = 32, and in particular the large radius of 51K and 52Ca (both having 32 neutrons), have attracted substantial attention.

One aim of the present study is therefore to shed light on several open questions in this region: how does the nuclear size of very neutron-rich nuclei evolve, and is there any evidence for the magicity of N = 32 from nuclear size measurements? We furthermore provide new data to test several newly developed nuclear models, which aim to understand the evolution of nuclear charge radii of exotic isotopes with large neutron-to-proton imbalance. So far, ab initio nuclear methods, allowing for systematically improvable calculations based on realistic Hamiltonians with nucleon–nucleon and three-nucleon potentials, have failed to explain the enhanced nuclear sizes beyond N = 28 in the calcium isotopes4,15. Meanwhile, nuclear density functional theory (DFT) using Fayans functionals has been successful in predicting the increase in the charge radii of isotopes in the proton-magic calcium chain10, as well as the kinks in proton-magic tin and lead12. All these theoretical approaches have, until now, been predominantly used to study the charge radii of even-Z isotopes. Here they will be applied to the odd-Z potassium isotopes (Z = 19).

Laser spectroscopy techniques yield the most accurate and precise measurements of the charge radius for radioactive nuclei. These highly efficient and sensitive experiments at radioactive ion beam facilities have expanded our knowledge of nuclear charge radii distributed throughout the nuclear landscape16. Laser spectroscopy achieves this in a nuclear-model-independent way by measuring the small perturbations of the atomic hyperfine energy levels due to the electromagnetic properties of the nucleus. Although these hyperfine structure effects are as small as one part in a million compared with the total transition frequency, they can now be measured with remarkable precision and efficiency, even for short-lived, weakly produced, exotic isotopes9.

The Collinear Resonance Ionization Spectroscopy (CRIS) experimental set-up at the ISOLDE facility of CERN allows very exotic isotopes to be studied with high resolution and high efficiency9,17. Relevant details of the ISOLDE radioactive beam facility and the CRIS set-up are depicted in Fig. 1a (Methods). With the CRIS technique, the energy differences between the atomic hyperfine transitions are measured by counting the resonantly ionized ions as a function of the laser frequency. If measurements are performed on more than one isotope, the difference in the mean-square charge radius of these isotopes can be obtained from the difference in the hyperfine structure centroid frequency of two isotopes (the isotope shift) with mass numbers A and A′: δνA,A′=νA − νA′.

a, The nuclei of interest were produced via nuclear reactions after a 1.4 GeV proton beam impinged onto a UCx target. These diffused out of the target, into an ion source and underwent surface ionization. The ion beam was then mass separated using a high-resolution separator (HRS), and subsequently cooled and bunched in a linear Paul trap (ISCOOL). The bunched ion beam was guided towards the CRIS beamline, where the ions were first neutralized in a charge-exchange cell (CEC) filled with potassium vapour. The neutral atoms were then delivered to the interaction region (IR) through the differential pumping region (DP). Here the bunched beam of atoms was collinearly overlapped with the laser pulses to achieve resonance laser ionization. The ionized radioactive potassium ions were deflected to a detection station, containing a removable MagneToF ion detector and a set of two plastic scintillator detectors labelled A and B. b,c, The left component of the 52K hyperfine structure spectrum measured with the MagneToF ion detector (b) and the scintillator detectors (c) as a function of the laser frequency detuning. The red line and shaded area in b indicate the expected position of the hyperfine structure peaks. d, The full hyperfine structure spectrum of 52K measured with the scintillator detectors as a function of the laser frequency detuning. The red line is the best fit. The inset is the hyperfine structure scheme corresponding to the full spectrum. Only coincidence events between the A and B detectors were processed by the data acquisition system (DAQ). Error bars show the statistical uncertainty.

To apply the CRIS method to study a light element such as potassium, where the optical transition exhibits a lower sensitivity to the nuclear properties, the long-term stability and accurate measurement of the laser frequency had to be investigated. The details of the relevant developments are presented in ref. 18, where the method was validated by measuring the mean-square charge radii of 38−47K isotopes with high precision. For the most exotic isotope, there was an extra challenge: a large isobaric contamination at mass A = 52, measured to be 2 × 104 times more intense than the 52K beam of interest. The resulting background rate was found to be an order of magnitude higher than that of the resonantly ionized 52K ions. In addition, this background rate was found to strongly fluctuate in time, making a measurement with ion detection impossible (see the low-frequency side of the hyperfine structure spectrum in Fig. 1b). Taking advantage of the short half-life of 52K (t1/2 = 110 ms) and the fact that the isobaric contamination is largely due to the stable 52Cr, an alternative detection set-up was developed, which can distinguish the radioactive 52K from the stable contamination. One thin and one thick scintillator detector (A and B in Fig. 1a) were installed behind the CRIS set-up, which were used to count the β-particles emitted by 52K implanted in a thin flange. The fluctuations in the background rate and signal-to-background ratio were notably improved, as seen in Fig. 1c. The full hyperfine structure spectrum of 52K is presented in Fig. 1d. The hyperfine structure spectra of 47−51K were remeasured with the standard CRIS method, and 50,51K were measured with both ion and β-particle detection as consistency checks. Thus, the isotope shifts of 47−52K could be determined (Methods).

The changes in the mean-square charge radii δ〈r2〉 are calculated from the isotope shift νA,A′ via

Here F, KSMS and KNMS are the atomic field shift, specific mass shift and normal mass shift factors, respectively (see Methods for details). Previously published charge radii of potassium isotopes were extracted from the isotope shifts using an F value calculated with a non-relativistic coupled-cluster (CC) method and an empirically determined KSMS value19.

Here, we employ the recently developed analytic response relativistic CC (ARRCC) theory20 (Methods), to calculate both the F and KSMS constants. The newly calculated value, F = −107.2(5) MHz fm−2, is more precise and in good agreement with the literature value (F = − 110(3) MHz fm−2). More importantly, the specific mass shift, a highly correlated atomic parameter, could be calculated from microscopic atomic theory. The calculated value, KSMS = −14.0(22) GHz u (where u is the atomic mass unit), is more precise than the empirical value, KSMS = −15.4(38) GHz u from ref. 9, and shows good agreement. Table 1 presents the isotope shifts, changes in mean-square charge radii and absolute charge radii of 36−52K that were extracted using these new atomic constants. The isotope shifts and charge radii have been re-evaluated using all available data, as described in the Methods. In Fig. 2a these changes in the mean-square charge radii are compared with values obtained using the atomic factors taken from ref. 19. Good agreement is obtained, while the systematic error due to the uncertainty on the atomic factors is clearly reduced.

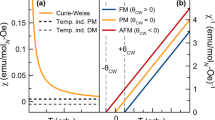

a, Changes in the mean-square charge radii of potassium isotopes. The results marked with squares are calculated using the newly calculated F and KSMS factors, whereas those with circle markers are obtained using the values from ref. 19. Error bars indicate statistical uncertainties, which in most cases are too small to be seen. In cases where multiple measurements were reported, the weighted mean of these values was used (Methods and Extended Data Table 1). The red and grey bands indicate the systematic error due to the uncertainty on these atomic parameters. The inset shows the changes in the mean-square charge radii of neighbouring elements (all relative to the radius of the isotope with neutron number N = 28). The agreement of the data for different isotopic chains above N = 28 is striking. b, The energy gaps obtained from the measured binding energies23,24 using the three-point filter25 for potassium (bottom), calcium (middle) and lead (top). Magic shell closures are shown at N = 28 and N = 126 and a subshell effect at N = 32. c, The odd–even staggering of the charge radii (Δ(3)r)14 of the potassium (bottom), calcium (middle) and lead (top) isotopes exhibit an inversion at the neutron magic numbers N = 28 and 126. No such an effect appears at N = 32. The error bars in b and c indicate statistical uncertainties. The neutron magic numbers of N = 28, 32 and 126 are indicated with the vertical grey solid and dotted lines in a–c.

Previously, the nuclear spin and parity of 52K was tentatively assigned to be Iπ = (2−) (ref. 21). Here, we have analysed our data assuming two other alternative spin options. Given that the I = 1 and I = 3 assumptions produce unrealistically small and large charge radii, respectively (Fig. 2a), our study further supports an I = 2 assignment.

The inset in Fig. 2a compares the changes in mean-square charge radii of several isotopic chains in this mass region up to Z = 26. A remarkable observation is that the charge radii beyond N = 28 follow the same steep increasing trend, irrespective of the atomic number. Beyond N = 32, data are only available for potassium isotopes (this work), and for open-shell manganese (Z = 25) isotopes22 for which no subshell closure at N = 32 has been reported. Both charge radii trends are very similar, with no pronounced kink at N = 32.

We further investigate the subshell gap at N = 32 by looking at the three-point filters of the experimentally measured ground-state properties. For binding energies B from refs. 23,24, we define \({\Delta }_{{\rm{1n}}}^{{\rm{(3)}}}B=\frac{1}{2}{(-1)}^{N}[B(N+1)-2B(N)+B(N-1)]\). We can then consider the energy gap as \(\Delta E=2[{\Delta }_{{\rm{1n}}}^{{\rm{(3)}}}B(N)-{\Delta }_{{\rm{1n}}}^{{\rm{(3)}}}B(N+1)]\) for even N (ref. 25). This quantity reaches a clear local maximum at magic numbers as shown in Fig. 2b. It becomes apparent that ΔE at N = 28 is notably larger than that at N = 32. It amounts to 1.6 MeV compared with 3 MeV at N = 20 and at N = 28 for the potassium isotopes. Similarly, ΔE at N = 32 in calcium, 2.2 MeV, is considerably smaller than the values of 4.2 MeV and 3.6 MeV at N = 20 and N = 28, respectively. From the charge radii, the odd–even staggering9 can also provide a signature of magicity. This is investigated by calculating the parameter \({\Delta }_{{\rm{1n}}}^{{\rm{(3)}}}r=\frac{1}{2}{(-1)}^{N+1}[r(N+1)-2r(N)+r(N-1)]\) as defined in ref. 14. At well-known shell gaps, this parameter is locally inverted, as shown for potassium and calcium at N = 28, and also for lead13 at N = 126 (Fig. 2c). However, no such inversion is seen at N = 32 for potassium. Thus, both the charge radii and the mass data of potassium are consistent with the absence of a neutron magic gap at N = 32. On the other hand, the local increase in ΔE at N = 32 seen in Fig. 2b is consistent with a local neutron subshell closure around Z = 20.

In the following, we compare the experimental data to recently developed nuclear theories. Previously, CC calculations based on the NNLOsat interaction26 were used to describe the nuclear charge radii for the stable doubly magic 40,48Ca isotopes and their immediate neighbours, as well as 51−53Ca (refs. 4,11). These calculations reproduced the absolute charge radii near 40,48Ca but failed to reproduce the observed large charge radii around N = 32. To compute the charge radii of the potassium isotopes, we extended the CC computations to open-shell nuclei by starting from a symmetry-breaking reference state27 (Methods). This allowed us to calculate the radii for the full chain of potassium isotopes using the NNLOsat interaction, and thus to study the trend beyond N = 28. This interaction was optimized to a set of experimental observables including binding energies and charge radii of selected nuclei up to A = 25. We also used the new ΔNNLOGO(450) interaction28, with Δ isobar degrees of freedom, which is constrained to properties of light nuclei up to mass A ≤ 4 and also by nuclear matter properties at the saturation point (Methods). In contrast to NNLOsat, this interaction more accurately describes the saturation density and symmetry energy in nuclear matter11,28. In Fig. 3a, we plot the changes in the mean-square charge radii with respect to the N = 28 isotope. This results in reduced systematic uncertainties near N = 28. Both interactions show a good agreement with the experimental results within the systematic uncertainty below N = 28, whereas the steep increase beyond N = 28 is largely underestimated (see also Extended Data Fig. 1). The absolute charge radii are presented in Fig. 3b. The reference isotope is 39K in this case, the only isotope with a measured absolute charge radius (Methods), resulting in the smallest systematic uncertainties around the stable isotopes. The NNLOsat interaction clearly overestimates the charge radii near stability, whereas the ΔNNLOGO(450) interaction shows better agreement, but still deviates towards neutron-rich isotopes. The differences between the interactions provide a lower estimate of a theoretical systematic uncertainty.

a, Mean-square charge radii relative to 47K, in which the systematic uncertainties near N = 28 are largely cancelled out. b, The absolute charge radii determined relative to that of stable 39K. Calculations were performed with the nuclear CC method using NNLOsat and ΔNNLOGO(450) interactions, and with the Fayans–DFT using the Fy(Δr, HFB) energy density functional. Error bars indicate statistical uncertainties, which in most cases are too small to be seen. The grey bands represent the systematic error due to the uncertainty on the atomic parameters.

The reason for the underestimation of the \(\updelta {\langle {r}^{2}\rangle }^{47,A}\) beyond N = 28 in the CC method can perhaps be attributed to the approximations employed. Our computations are limited to single and double excitations in the cluster amplitudes; they preserve axial symmetry and are lacking angular momentum restoration; the employed interactions are at next-to-next-to-leading order in the power counting; higher-order effects, such as additional two-body contact interactions and four-body forces, are neglected.

DFT is the method of choice for heavy systems. Nuclei with Z ≈ 20 cover the region where both methods, DFT and CC, can be successfully applied. Our DFT calculations use in particular the Fayans functional Fy(Δr, HFB)29 (Methods), which was developed with a focus on charge radii. This method closely reproduces the absolute charge radii of calcium isotopes, including the steep increase beyond N = 28 (ref. 10). Furthermore, Fy(Δr, HFB) reproduces the absolute radii of the magic tin12 and cadmium30 isotopes, as well as the odd-Z copper isotopes9. It should be noted, however, that the potassium isotopes are a lighter system in which the polarization effects of the odd proton are expected to be stronger than in the heavier copper isotopes. To account for that, we extended the Fayans–DFT framework to allow for deformed HFB solutions. The isotopic chain contains odd–odd nuclei and the present DFT and CC treatment does not allow a clean spin selection for these. Consequently, the calculations provide an averaged description for the odd–odd isotopes. As seen in Fig. 3b (and Extended Data Fig. 2), except for the neutron-poor side, Fy(Δr, HFB) calculations reproduce the average global trend well, in particular the steep increase above N = 28. However, this model grossly overestimates the odd–even staggering of the radii. This is very well captured by the CC calculations, owing to the fact that these describe in detail the many-body correlations (Methods). In nuclear DFT, local many-body correlations are treated less precisely.

In conclusion, the charge radii show no signature of a magic shell gap at N = 32, which is not in contradiction with the small subshell effect seen in the masses of potassium isotopes. The comparison of the experimental results with theoretical calculations highlights our limited understanding of the size of neutron-rich nuclei, and will undoubtedly trigger further developments in nuclear theory. In addition, fully understanding the nuclear structure in this region requires measurements of additional charge radii across N = 32 and the next proposed magic number, N = 34.

Methods

The CRIS technique

The schematic layout of the CRIS set-up is presented in Fig. 1a. The mass selected ions were cooled and bunched in the ISCOOL device, which operated at 100 Hz, the duty cycle of the CRIS experiment. The ion bunches typically have a 6 μs temporal width, corresponding to a spatial length of around 1 m. First, the bunched ion beam was neutralized in the CRIS beamline through collisions with potassium atoms in the charge-exchange cell (CEC). The remaining ions were deflected just after the CEC with an electrostatic deflector plate. In addition, atoms that were produced in highly excited states through the charge-exchange process were field ionized and deflected out of the beam. The beam of neutral atoms passed through the differential pumping region and arrived in the 1.2 m interaction region maintained at a pressure of 10−10 mbar. Here the atom bunch was collinearly overlapped with three laser pulses, which were used to excite and ionize the potassium atoms in a step-wise manner. A detailed study of this particular resonance ionization scheme can be found in ref. 18. In the interaction region, ions can also be produced in non-resonant processes, introducing higher background rates31. Normally, the ions created in the interaction region are guided towards an ion detector (MagneToF). This technique was used for the measurement of 47−51K. The 51K isotope was produced at a rate of less than 2,000 particles per second and its hyperfine structure spectrum was measured in less than 2 h. The study of 52K, however, required a still more selective detection method. This isotope, produced at a rate of about 360 particles per second, is an isobar of the most abundant stable chromium isotope, which is the main contaminating species in the A = 52 beam, with an intensity of 6 × 106 particles per second. To avoid the detection of the non-resonantly ionized 52Cr, the CRIS set-up was equipped with a decay detection station, placed behind the end flange of the beamline. The MagneToF detector was removed from the path of the ion beam, and the ionized bunches were implanted into a thin aluminium window of 1 mm thickness, allowing the transmission of β-particles with energies larger than 0.6 MeV. The decay station behind this window consisted of one thin and one thick scintillator detector (A and B in Fig. 1a) for a coincidence detection of β-particles. The dimensions of the detectors were 1 mm × 6 cm × 6 cm and 6 cm × 6 cm × 6 cm. The β-particle counts detected in coincidence were recorded by the data acquisition system (DAQ) together with the laser frequency detuning. The DAQ recorded the number of events in the detectors with a timestamp. The timestamp of the proton bunches impinging into the target of ISOLDE was also recorded and used to define the time gates in the data analysis.

Laser system

A three-step resonance ionization scheme was used in this experiment. The laser light for the first excitation step was produced by a continuous-wave titanium-sapphire (Ti:Sa) laser (M-Squared SolsTiS) pumped by an 18 W laser at 532 nm (Lighthouse Photonics). To avoid optical pumping to dark states due to long interaction times, this continuous-wave light was ‘chopped’ into 50 ns pulses at a repetition rate of 100 Hz by using a Pockels cell17. The wavelength of this narrowband laser was tuned to probe the hyperfine structure of the 4s 2S1/2 → 4p 2P1/2 transition at 769 nm. Atoms in the excited 4p 2P1/2 state were subsequently further excited to the 6s 2S1/2 atomic state by a pulsed dye laser (Spectron PDL SL4000) with a spectral bandwidth of 10 GHz. This dye laser was pumped by a 532 nm Nd:YAG laser (Litron TRLi 250-100) at a 100 Hz repetition rate. The fundamental output of the same Nd:YAG laser (1,064 nm) was used for the final non-resonant ionization. The arrival of ion bunches and laser pulses in the interaction region was synchronized and controlled using a multi-channel pulse generator (Quantum Composers 9520 Series).

Charge radii extraction

The perturbation of the atomic states caused by the different nuclear charge distribution in isotopes leads to small differences in the atomic transition frequency, δνAA′, between centroids (νA, νA′) of the hyperfine structure of two isotopes with mass number A and A′. The isotope shifts of 48−52K were extracted from the hyperfine structure spectra, analysed using the SATLAS32 Python package, as displayed in third column of Extended Data Table 1, along with all available results from literature. More details on the analysis process can be found in Ref. 18. The changes in the nuclear mean-square charge radii of 36−52K can then be extracted from the isotope shifts using:

where KMS and F are the atomic mass shift and field shift, m stands for the nuclear mass of isotopes A, A′ and an electron. The nuclear mass was obtained by subtracting the mass of the electrons from the experimentally measured atomic mass reported in ref. 23. The atomic constants KMS and F were calculated using the atomic ARRCC method as described below. The root-mean-square charge radii of these isotopes are:

where R39 is the charge radius of 39K taken from ref. 33.

Evaluation of the isotope shifts and charge radii

The isotope shifts of potassium isotopes have been measured using several different techniques over many years, ranging from magneto-optical trap experiments34 to laser spectroscopy of thermal35,36,37 and accelerated beams38,5,18, relying on photon and ion detection. The available results in refs. 34,35,36,37,38 are referenced to the stable 39K isotope, and are presented in the second column of Extended Data Table 1. The isotope shifts in refs. 5,18 and this work, shown in the third column of Extended Data Table 1, were extracted with respect to 47K. The systematic error from the experiments is given in curly brackets. Note that the systematic uncertainties in collinear laser spectroscopy experiments are mostly related to the inaccuracy of the acceleration voltage. In this work, the systematic uncertainty was negligible thanks to the well-calibrated high-precision voltage divider (with a relative uncertainty of 5 × 10−5) from the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB). To compile a consistent dataset with reliable evaluation of uncertainties, the following steps were taken:

-

(1)

The isotope shifts obtained with respect to 47K were recalculated relative to 39K to link all data to the same reference. For this, the weighted average of all available δν47,39 isotope shifts from refs. 5,18 was used as a reference. These rereferenced values are listed in the fifth column of Extended Data Table 1 and their uncertainty was increased due to the additional error associated with \({\overline{\delta \nu }}^{39,47}\) (bold value in column six). Note that the systematic errors are always taken into account using the linear model 39, σ = σsys + σstat.

-

(2)

Next, the final isotope shift of each potassium isotope, \({\overline{\updelta \nu }}^{39,A}\) (shown in the sixth column of Extended Data Table 1), was calculated as the weighted average (\(\hat{x}\)) of the available results (xi) using:

$$\hat{x}=\frac{{\Sigma }_{i = 1}^{n}({x}_{i}{\sigma }_{i}^{-2})}{{\Sigma }_{i = 1}^{n}{\sigma }_{i}^{-2}},$$(4)where σi is the total uncertainty of the ith measurement. The error of the weighted mean was obtained using:

$${\sigma }_{\hat{x}}=\sqrt{\frac{1}{{\Sigma }_{i = 1}^{n}{\sigma }_{i}^{-2}}},$$(5)accounting for possible over-, or underdispersion using:

$${\hat{\sigma }}_{\overline{x}}^{2}={\sigma }_{\overline{x}}^{2}{\chi }^{2},$$(6)where χ2 is the reduced chi-squared.

-

(3)

These evaluated isotope shifts were used to extract the changes in the mean-square charge radii (column 7 of Extended Data Table 1) using the new theoretical values for the atomic field and mass shifts, obtained in this work. The systematic errors on δ〈r2〉 shown in the square brackets of column 7 of Extended Data Table 1 come from the uncertainty of the calculated atomic field and mass shifts. Note that the contribution from the mass uncertainty is negligible due to the small relative error (for example, \(\frac{\updelta m}{m}<1{0}^{-8}\) for both 51K and 52K). The absolute charge radii of all potassium isotopes (last column of Extended Data Table 1) were then calculated using equation (3) relative to the absolute radius of the stable 39K (ref. 33).

Atomic CC calculations

The wavefunction of an atomic state with a closed-shell and a valence orbital electronic configuration can be expressed using the CC theory ansatz as

where \(\left|{\varPhi }_{\mathrm{v}}\right\rangle\) is the mean-field wavefunction and \(\tilde{S}\) is the CC excitation operator. We further divide as \(\tilde{S}=T+{S}_{\mathrm{v}}\) to distinguish electron correlations without involving the valence electron (T) and involving the valence electron (Sv). In the analytic response procedure, the first-order energy of the atomic state is obtained by solving the equation

where Hat is the atomic Hamiltonian, Hint is the interaction Hamiltonian, \(\left|{\varPsi }_{\mathrm{v}}^{(0)}\right\rangle\) is the unperturbed wavefunction with energy \({E}_{\mathrm{v}}^{(0)}\), and \(\left|{\varPsi }_{\mathrm{v}}^{(1)}\right\rangle\) is the first-order perturbed wavefunction with the first-order energy \({E}_{\mathrm{v}}^{(1)}\). Here, Hat involves the Dirac terms, the nuclear potential, the lower-order quantum electrodynamics corrections and the electron–electron interactions due to the longitudinal and transverse photon exchanges, whereas Hint is either the field-shift operator due to the Fermi nuclear charge distribution in the evaluation of F or the relativistic form of the SMS operator for the determination of KSMS. In the ARRCC theory, the unperturbed and perturbed wavefunctions are obtained by expanding

where λ is the perturbation parameter. After solving the amplitudes of both the unperturbed and perturbed CC operators, as described in ref. 20, we evaluate the first-order energy as

in which the subscript c indicates the connected terms. We have considered all possible single, double and triple electronic excitation configurations in our ARRCC method for performing the atomic calculations.

Nuclear CC calculations

The nuclear CC calculations start from the intrinsic Hamiltonian including two- and three-nucleon forces

with Pi (Pj) the momentum of ith (jth) nucleon in the nucleus. The nuclear CC wavefunction is written as \(\left|\varPsi \right\rangle ={\mathrm{e}}^{T}\left|{\varPhi }_{0}\right\rangle\), where the cluster operator T is a linear combination of n-particle-n-hole excitations truncated at the two-particle-two-hole level, commonly known as the CC with singles-and-double excitations (CCSD). The reference state \(\left|{\varPhi }_{0}\right\rangle\) is restricted to axial symmetry and is constructed in the following way. We start by solving the self-consistent Hartree–Fock equations by assuming that the most energetically favourable configuration is obtained by filling the states with the lowest angular momentum projection along the z axis (prolate deformation). Subsequently, we construct a natural orbital basis by diagonalizing the density matrix obtained from second-order perturbation theory40. Finally, we normal-order the Hamiltonian (equation (11)) with respect to the natural orbital mean-field solution, keeping up to two-body normal-ordered contributions. The model-space used in our calculations is given by 13 major harmonic oscillator shells (Nmax = 12) with the oscillator frequency ℏΩ = 16 MeV. The three-body interaction has the additional cutoff on allowed three-particle configurations E3max = N1 + N2 + N3 ≤ 16, with Ni = 2ni + li. This model-space is sufficient to converge the radii of all of the potassium isotopes considered in this work to within ~1%. We calculate the expectation value of the squared intrinsic point proton radius, that is \(\langle O\rangle =\langle 1/Z{\sum }_{i\,{<}\,j}{({{\bf{r}}}_{i}-{{\bf{r}}}_{j})}^{2}{\updelta }_{{t}_{z},-1}\rangle\). The CC expectation value of the operator O is given by \(\left\langle {\varPhi }_{0}\right|\left(1+\varLambda \right){\mathrm{e}}^{-T}O{\mathrm{e}}^{T}\left|{\varPhi }_{0}\right\rangle =\left\langle {\varPhi }_{0}\right|\left(1+\varLambda \right)\overline{O}\left|{\varPhi }_{0}\right\rangle\); here \(\left\langle {\varPhi }_{0}\right|(1+\varLambda){\mathrm{e}}^{-T}\) is the left ground-state and Λ is the linear combination of one-hole-one-particle and two-hole-two-particle de-excitation operators (see, for example, ref. 41 for details). To obtain the charge radii we add finite proton/neutron, the relativistic Darwin–Foldy and spin–orbit corrections to the point proton radii. We note that the spin–orbit corrections are computed consistently as an expectation value within the CC approach, see ref. 11.

The chiral interaction NNLOsat (ref. 26) was constrained by nucleon–nucleon scattering data, and binding energies and charge radii of nuclei up to oxygen. It includes nucleon–nucleon and three-nucleon forces up to next-to-next-to leading order in the Weinberg power counting. The newly constructed ΔNNLOGO(450) interaction by the Gothenburg–Oak Ridge (GO) collaboration28 also includes Δ isobar degrees of freedom, has a cutoff of 450 MeV, and is also limited to NNLO. Its construction started from the interaction of ref. 42 and its low-energy constants are constrained by the empirical saturation point (density and energy) and the symmetry energy of nuclear matter, by pion–nucleon scattering43, nucleon–nucleon scattering and by selected properties of the A ≤ 4 nuclei. A second interaction, ΔNNLOGO(394), was similarly constructed but with a cutoff of 394 MeV. By construction, the ΔNNLOGO interactions yield an accurate saturation point and symmetry energy of nuclear matter. They are also accurate for binding energies and radii, see ref. 28 for details.

To look at the sensitivities in the changes in the mean-square change radii, Extended Data Fig. 1a compares results from the newly developed interactions with NNLOsat. Although there are differences below N = 28, all interactions yield essentially identical results beyond N = 28. This suggests that charge radii beyond N = 28 are insensitive to details of chiral interactions at next-to-next-to-leading order.

To shed more light on this finding, Extended Data Fig. 1b compares results from deformed mean-field calculations with CCSD computations for two different interactions. The 1.8/2.0(EM) interaction44 contains contributions at next-to-next-to-next-to-leading order and thereby differs from the interactions used in this work. First, for the ΔNNLOGO(394) interaction, mean-field and CC yield essentially the same results for N > 28, although CC includes many more wavefunction correlations. Second, for the 1.8/2.0(EM) interaction, mean-field and CC results differ notably by the strong odd–even staggering, which is a correlation effect. None of the interactions explain the dramatic increase in the charge radii beyond N = 28.

DFT calculations

For the DFT part of this work, we use the non-relativistic Fayans functional in the form of ref. 45. This functional is distinguished from other commonly used nuclear DFT in that it has additional gradient terms at two places, namely in the pairing functional and in the surface energy. The gradient terms allow, among other features, a better reproduction of the isotopic trends of charge radii46. This motivated a refit of the Fayans functional to a broad basis of nuclear ground-state data with additional information on changes in mean-square charge radii in the calcium chain4,29. We use here Fy(Δr, HFB) from refs. 4,29, which employed the latest data on calcium radii. It is only with strong gradient terms that the trends of radii in calcium can be reproduced at all, in particular its pronounced odd–even staggering, yet there is a slight tendency to exaggerate the staggering. It was found later that Fy(Δr, HFB) performs very well in describing the trends of radii in cadmium and tin isotopes12,30. Here we test it again for the potassium chain next to calcium. For all practical details pertaining to our Fayans–DFT calculations, we refer the reader to ref. 29.

All of the above-mentioned calculations with Fy(Δr, HFB) were done in a spherical representation. This choice could be called into question for nuclei far from shell closures, and more so for odd nuclei where the odd nucleon induces a certain quadrupole moment. The new feature in the present calculations is that we use a code in the axial representation that allows for deformations if the systems wants any. Figure 3 shows the result from the deformed code47, adapted for the Fayans functional. In Extended Data Fig. 2 we illustrate the effect of deformation by comparison with spherical calculations. The effects are small, but show that there is no uncertainty due to symmetry restrictions. The lack of angular momentum projection in DFT calculations induces a systematic error on the charge radii. We have estimated this error from the angular momentum spread to be below 0.005 fm on average, thus having no consequences for the predicted trends.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. All other data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Change history

24 February 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-021-01192-5

References

Huck, A. et al. Beta decay of the new isotopes 52K, 52Ca, and 52Sc; a test of the shell model far from stability. Phys. Rev. C 31, 2226–2237 (1985).

Wienholtz, F. et al. Masses of exotic calcium isotopes pin down nuclear forces. Nature 498, 346–349 (2013).

Rosenbusch, M. et al. Probing the N = 32 shell closure below the magic proton number Z = 20: mass measurements of the exotic isotopes 52,53K. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 202501 (2015).

Garcia Ruiz, R. F. et al. Unexpectedly large charge radii of neutron-rich calcium isotopes. Nat. Phys. 12, 594–598 (2016).

Kreim, K. et al. Nuclear charge radii of potassium isotopes beyond N = 28. Phys. Lett. B 731, 97 – 102 (2014).

Nörtershäuser, W. et al. Nuclear charge radii of 7,9,10Be and the one-neutron halo nucleus 11Be. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 062503 (2009).

Marsh, B. A. et al. Characterization of the shape-staggering effect in mercury nuclei. Nat. Phys. 14, 1163–1167 (2018).

Yang, X. F. et al. Isomer shift and magnetic moment of the long-lived 1/2+ isomer in \({\,}_{30}^{79}{\mathrm{Zn}}_{49}\): signature of shape coexistence near 78Ni. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 182502 (2016).

de Groote, R. et al. Measurement and microscopic description of odd–even staggering of charge radii of exotic copper isotopes. Nat. Phys. 16, 620–624 (2020).

Miller, A. J. et al. Proton superfluidity and charge radii in proton-rich calcium isotopes. Nat. Phys. 15, 432–436 (2019).

Hagen, G. et al. Neutron and weak-charge distributions of the 48Ca nucleus. Nat. Phys. 12, 186–190 (2016).

Gorges, C. et al. Laser spectroscopy of neutron-rich tin isotopes: a discontinuity in charge radii across the N = 82 shell closure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 192502 (2019).

Anselment, M. et al. The odd-even staggering of the nuclear charge radii of Pb isotopes. Nucl. Phys. A 451, 471 – 480 (1986).

Farooq-Smith, G. J. et al. Probing the 31Ga ground-state properties in the region near Z = 28 with high-resolution laser spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. C 96, 044324 (2017).

Somà, V., Navrátil, P., Raimondi, F., Barbieri, C. & Duguet, T. Novel chiral hamiltonian and observables in light and medium-mass nuclei. Phys. Rev. C 101, 014318 (2020).

Campbell, P., Moore, I. & Pearson, M. Laser spectroscopy for nuclear structure physics. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 86, 127–180 (2016).

de Groote, R. P. et al. Use of a continuous wave laser and Pockels cell for sensitive high-resolution collinear resonance ionization spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 132501 (2015).

Koszorús, A. et al. Precision measurements of the charge radii of potassium isotopes. Phys. Rev. C 100, 034304 (2019).

Martensson-Pendrill, A. M., Pendrill, L., Salomonson, A., Ynnerman, A. & Warston, H. Reanalysis of the isotope shift and nuclear charge radii in radioactive potassium isotopes. J. Phys. B 23, 1749–1761 (1990).

Sahoo, B. K. et al. Analytic response relativistic coupled-cluster theory: the first application to indium isotope shifts. N. J. Phys. 22, 012001 (2020).

Perrot, F. et al. β-decay studies of neutron-rich K isotopes. Phys. Rev. C 74, 014313 (2006).

Heylen, H. et al. Changes in nuclear structure along the Mn isotopic chain studied via charge radii. Phys. Rev. C 94, 054321 (2016).

Wang, M. et al. The AME2016 atomic mass evaluation (II). Tables, graphs and references. Chin. Phys. C 41, 030003 (2017).

Michimasa, S. et al. Magic nature of neutrons in 54Ca: first mass measurements of 55−57Ca. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 022506 (2018).

Satuła, W., Dobaczewski, J. & Nazarewicz, W. Odd-even staggering of nuclear masses: pairing or shape effect? Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 3599–3602 (1998).

Ekström, A. et al. Accurate nuclear radii and binding energies from a chiral interaction. Phys. Rev. C 91, 051301 (2015).

Novario, S. J., Hagen, G., Jansen, G. R. & Papenbrock, T. Charge radii of exotic neon and magnesium isotopes. Phys. Rev. C 102, 051303(R) (2020).

Jiang, W. G. et al. Accurate bulk properties of nuclei from A = 2 to ∞ from potentials with Δ isobars. Phys. Rev. C 102, 054301 (2020).

Reinhard, P.-G. & Nazarewicz, W. Toward a global description of nuclear charge radii: exploring the Fayans energy density functional. Phys. Rev. C 95, 064328 (2017).

Hammen, M. et al. From calcium to cadmium: testing the pairing functional through charge radii measurements of 100−130Cd. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 102501 (2018).

Koszorús, A. et al. Resonance ionization schemes for high resolution and high efficiency studies of exotic nuclei at the CRIS experiment. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 463, 398–402 (2020).

Gins, W. et al. Analysis of counting data: development of the SATLAS Python package. Comput. Phys. Commun. 222, 286–294 (2018).

Fricke, G. & Heilig, K. in Nuclear Charge Radii Vol. 20 (ed. Schopper, H.) https://doi.org/10.1007/10856314_21 (Landolt-Börnstein - Group I Elementary Particles, Nuclei and Atoms, Vol. 20, Springer, 2004).

Behr, J. A. et al. Magneto-optic trapping of β-decaying 38Km, 37K from an on-line isotope separator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 375–378 (1997).

Falke, S., Tiemann, E., Lisdat, C., Schnatz, H. & Grosche, G. Transition frequencies of the D lines of 39K, 40K, and 41K measured with a femtosecond laser frequency comb. Phys. Rev. A 74, 032503 (2006).

Touchard, F. et al. Isotope shifts and hyperfine structure of 38−47K by laser spectroscopy. Phys. Lett. B 108, 169–171 (1982).

Bendali, N., Duong, H. T. & Vialle, J. L. High-resolution laser spectroscopy on the D1 and D2 lines of 39,40,41K using RF modulated laser light. J. Phys. B 14, 4231–4240 (1981).

Rossi, D. M. et al. Charge radii of neutron-deficient 36K and 37K. Phys. Rev. C 92, 014305 (2015).

Petersen, P. et al. Models for combining random and systematic errors. Assumptions and consequences for different models. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 39, 589–595 (2001).

Tichai, A., Müller, J., Vobig, K. & Roth, R. Natural orbitals for ab initio no-core shell model calculations. Phys. Rev. C 99, 034321 (2019).

Bartlett, R. J. & Musiał, M. Coupled-cluster theory in quantum chemistry. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 291–352 (2007).

Ekström, A., Hagen, G., Morris, T. D., Papenbrock, T. & Schwartz, P. D. Δ isobars and nuclear saturation. Phys. Rev. C 97, 024332 (2018).

Siemens, D. et al. Reconciling threshold and subthreshold expansions for pion-nucleon scattering. Phys. Lett. B 770, 27–34 (2017).

Hebeler, K., Bogner, S. K., Furnstahl, R. J., Nogga, A. & Schwenk, A. Improved nuclear matter calculations from chiral low-momentum interactions. Phys. Rev. C 83, 031301 (2011).

Fayans, S. A. Towards a universal nuclear density functional. JETP Lett. 68, 169–174 (1998).

Minamisono, K. et al. Charge radii of neutron deficient 52,53Fe produced by projectile fragmentation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 252501 (2016).

Stoitsov, M. et al. Axially deformed solution of the Skyrme–Hartree–Fock–Bogoliubov equations using the transformed harmonic oscillator basis (II) HFBTHO v2.00d: a new version of the program. Comput. Phys. Commun. 184, 1592–1604 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the ISOLDE collaboration and technical teams. This work was supported in part by the National Key R&D Program of China (contract number 2018YFA0404403); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 11875073); the BriX Research Program number P7/12, FWO-Vlaanderen (Belgium), GOA 15/010 from KU Leuven; ERC Consolidator grant number 648381 (FNPMLS); the STFC consolidated grant numbers ST/L005794/1, ST/L005786/1, ST/P004423/1 and Ernest Rutherford grant number ST/L002868/1; the EU Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme through ENSAR2 (grant number 654002); the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Nuclear Physics under grant numbers DE-SC0021176, DE-00249237, DE-FG02-96ER40963 and DE-SC0018223 (SciDAC-4 NUCLEI collaboration). This work received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement number 758027), the Swedish Research Council grant number 2017-04234 and the Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education (STINT) grant number IG2012-5158. B.K.S. acknowledges the use of the Vikram-100 HPC cluster of the Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad, for atomic calculations. Computer time was provided by the Innovative and Novel Computational Impact on Theory and Experiment (INCITE) programme. This research used resources of the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility and of the Compute and Data Environment for Science (CADES), located at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, which is supported by the Office of Science of the Department of Energy under contract number DE-AC05-00OR22725.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Á.K., X.F.Y., S.W.B., J.B., C.L.B., M.L.B., T.E.C., B.S.C., R.P.d.G., K.T.F., S.F., R.F.G.R., F.P.G., A.K., G.N., C.M.R., A.R.V. and S.G.W. performed the experiment. Á.K. and X.F.Y. led the experiment and Á.K., X.F.Y., R.F.G.R. and S.W.B. designed, simulated and installed the β-particle detection system. Á.K. and X.F.Y. performed the data analysis. W.G.J., G.H., T.P., A.E., G.R.J., S.J.N. and C.F. developed the ΔNNLOGO interactions and performed the CC calculation. W.N., P.-G.R. and M.K. performed the DFT calculation. B.K.S. performed the atomic physics calculations. Á.K., X.F.Y., G.N., W.N., P-G.R., G.H. and T.P. prepared the manuscript. Á.K., X.F.Y., G.N., W.N., P.-G.R. and G.H. prepared the figures. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript at all stages. Á.K. and X.F.Y. contributed equally to this work. Affiliation 2 is the primary affiliation for X.F.Y.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Physics thanks Gianluca Colo, Jens Dilling and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Experimental charge radii and the coupled-cluster calculations for 36−52K.

a, Changes in mean-square charge radii calculated with the newly developed interactions, ΔNNLOGO(394) and ΔNNLOGO(450), and the NNLOsat, compared to experimental data. All calculations underestimate the charge radii of neutron-rich isotopes beyond N = 28. Error bars represent the statistical uncertainty. b, Changes in mean-square charge radii calculated using different theoretical approaches, deformed mean-field (MF) and coupled cluster with singles-and-double excitations (CCSD), and for two different interactions. All calculations are consistent.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Absolute charge radii and the Fayans density functional calculations for 36−52K.

Charge radii along the chain of potassium isotopes from spherical as well as deformed calculations with the functional Fy(Δr,HFB) are compared to experimental data. The predictions of these two calculations are in excellent agreement with each other. Error bars show the statistical uncertainty, which in most of the cases are too small to be seen. The gray band corresponds to the systematic uncertainly of the experimental data due to the atomic parameters.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

CSV data file.

Source Data Fig. 3

CSV data file.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

CSV data file.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

CSV data file.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koszorús, Á., Yang, X.F., Jiang, W.G. et al. Charge radii of exotic potassium isotopes challenge nuclear theory and the magic character of N = 32. Nat. Phys. 17, 439–443 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-020-01136-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-020-01136-5

This article is cited by

-

Nuclear charge radius predictions by kernel ridge regression with odd–even effects

Nuclear Science and Techniques (2024)

-

Control and data acquisition system for collinear laser spectroscopy experiments

Nuclear Science and Techniques (2023)

-

Machine learning in nuclear physics at low and intermediate energies

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2023)

-

Commissioning of a high-resolution collinear laser spectroscopy apparatus with a laser ablation ion source

Nuclear Science and Techniques (2022)

-

Precision mass measurement of lightweight self-conjugate nucleus 80Zr

Nature Physics (2021)